A recent (May 23, 2018) Invasive Species Council blog takes aim at the “rapidly growing international and cross-disciplinary movement” called Compassionate Conservation” – a movement that promotes “the protection of wild animals as individuals within conservation practice and policy”.

The blog is titled “Compassionate conservation or misplaced compassion”. The author is Peter Fleming, an ecologist who works on the biology, ecology and management of invasive predators and their prey. He is also Adjunct Professor of Ecosystem Management, University of New England and Principal Research Scientist with New South Wales Department of Primary Industries.

Having spent “a career trying to undo the damage caused by invasive introduced animals to the Australasian environmental and agricultural values”, Fleming’s concerns deserve serious consideration.

He begins by taking offense with the term Compassionate Conservation, contending “most conservationists” after all, “are compassionate [because] without compassion for the living world they would not be interested in conserving it.”

He then excludes adherents of Compassionate Conservation from “most conservationists”, stating these apparently pseudo-conservationists embody “the capacity to do harm to the cause of conservation in Australia and elsewhere because [Compassionate Conservation] has little foundation in biology. It is animal liberation dressed up as conservation science.”

Fleming differentiates real conservationists from the posers by the former’s disregard for the individual animal. Real conservationists, like Fleming, are comfortable excluding individuals of a species from their compassion and their conservation. Whereas, a primary tenant of Compassionate Conservation believes individuals matter.

Fleming’s brand of “lower case compassion”, believes it is “sometimes more ethical to kill animals than not to. Conservation of individuals, species and ecosystems often depends on that ethic. When you must kill individuals of one species to preserve the very existence of another species and prevent it from careening or staggering to extinction, it is a moral act. To stand by and watch extinction happen in the guise of compassion is reprehensible”, Fleming opines.

Fleming refers to European wild rabbits as a case in point, saying “Speciation and extinction are happening all the time, but humans are accelerating the latter through massive changes by the introduction of species from different ecosystems”,

Compassionate Conservationist, Arian Wallach, of the University of Adelaide, Australia, and the University of Haifa, Israel, reminds traditional conservationists like Fleming that “Killing rabbits, and other unwanted species, has not provided the cure to Australia’s environmental problems, because ultimately these problems are of our own making. Persecution of Australia’s apex predator, the dingo, alongside other human activities such as overgrazing with livestock, have been highly detrimental. Rabbits are merely the scapegoat. Dingoes, particularly when socially stable, can limit rabbit densities. Providing space for dingoes to assume their ecological function offers a way forward that is both effective and ethical. It is also important to consider that rabbits are a threatened species in their native range, and they provide many ecological benefits – not just harms.”

Fleming dismisses Wallach’s assertion as “untrue”, defending the “killing” of “many rabbits” through such extraordinary means as “the release of myxoma virus in the 1950s and rabbit haemorrhagic disease in the 1990s” and the “ongoing poisoning, ripping and shooting” of millions of rabbits as “the only effective way of limiting their ecological and agricultural damage.”

And yet, after nearly 70 years of killing, the problem persists…

Fleming’s contention that Compassionate Conservation is merely “animal liberation dressed up as conservation science” seems intended to direct our attention away from the fact that his tortured reasoning is actually a desperate attempt to regain these failing methodologies’ stature as legitimate conservation science.

Is there any scientific evidence to support Compassionate Conservation?

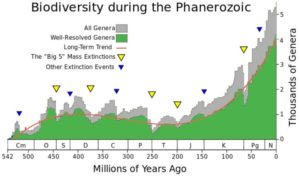

In 2017, the Journal of Ecography published a study produced by Erick Lundgren of Arizona State University and the aforementioned Arian Wallach, which found that invasive introductions “significantly increased megafauna richness, numerically replacing many of the Pleistocene megafauna that were lost around 50,000 years ago.”

“This study challenges” Fleming’s “fundamental ideas surrounding ‘invasive species’ and shows that the redistribution of species is ‘rewilding’ the world. The global decline of megafauna is driven by habitat loss, changes in land-use, and overhunting. Despite this, some megafauna have found refuge in new habitats through introductions.”

Two competing philosophies; to kill or not to kill

Traditional Conservation is best described, I think, by Merritt Clifton, as being “deeply rooted, if largely unawares, in the religious notion that there once was a perfect Garden of Eden, ordained by God but destroyed by mankind. Traditional conservation seeks to protect biodiversity by deciding which species ‘belong’ in any given place, as positioned by God or ‘nature’ exclusive of human activity.

“Any species whose presence might challenge ordained ‘natives’ are persecuted as ‘invasive,’ even if the habitat has changed so much that the ‘invasive’ species are better suited than the ‘natives’ to surviving there.”

Compassionate Conservation is best described, I think, by Lundgren and Wallach as a recognition of the irreversible “rewilding” of the world. That is, a recognition of the fact that invasive populations serve as “critical buffers against extinction”. For example, consider the world’s only population of wild dromedary camel which thrive in Australia today despite being extinct in their native range for some 2,000 years or more. Should they be killed off as invasive?

Fleming concedes Compassionate Conservation sounds “noble and admirable” but warns that “respecting the rights of one individual or group of animals may involve trampling on the rights of others. Invasive animals do exactly that, often with catastrophic effects on the survival of other animal and plant species, and completely restructuring ecosystems. Often humans have to kill individuals of one species to achieve conservation of broader intrinsic, economic and environmental values.”

Is that true? Or is it simply the short view? Seventy years of killing rabbits, home to the world’s only wild dromedary camels – at what point do we recognize an invasive species as having established itself in the ecosystem?

Lundgren explains that when we end the war on invasive species we will discover they come with many benefits, including they “can consume plant matter indigestible to smaller herbivores, which may [then] reduce fire frequency, accelerate nutrient cycling, and shape plant communities.” That is, “rewilding” replenishes the earth, making it better not worse – as feared by traditionalists.

For instance, Lundgren and Wallach found that, “of the world’s 76 existing megafauna species, 22 have introduced populations.” Of these 22 invasive species, “almost 50% are either threatened or extinct in their historic native ranges.” Meaning, their “invasion” status may be nature’s way of forestalling extinction.

In the April 25, 2018 edition of Conservation Biology, Lundgren and Wallach further explain “A significant proportion of Earth’s wildlife has been erased, not from the world, but from our collective” or traditional “depiction of nature. Even the most noticeable animals, terrestrial herbivorous megafauna, have been made nominally invisible. Wildlife outside native ranges are conspicuously missing from conservation data sets, distribution maps, population estimates, and conservation statuses.”

That is, if we are to listen only to the traditional conservationists we would conclude we are in the midst of a mass extinction. In fact, “Introduced megafauna are a wonder of the Anthropocene,” (the time humans dominated Earth), “hidden in plain sight.” (Invisible Megafauna)

“Many regions have an immortalized moment ‘when the first white man stepped off the boat,’ heralding the beginning of Western civilization and the end of nature. Organisms caught in humanity’s globalization currents were branded products of man, not of nature. Conservation databases depict Australia as empty of megafauna, despite being home to eight species, because they became established after James Cook landed at Botany Bay in 1770.”

“A similar number of species are excluded from formal accounts of North American megafauna because they arrived after Christopher Columbus.

“Valuing only ideals of untouched wilderness excludes much if not all the biosphere, perpetuates colonial ideologies, and fails to acknowledge thousands of years of human ecology exploitation.

“The bottom line, despite much reckless talk of an ‘extinction crisis,’ is the fact that all continents have more megafauna species today than in the Holocene.”

Despite the fact that humans are responsible for the extinction of the wooly mammoth, giant ground sloth, and saber-toothed cat in the Pleistocene and “the current decline of 60% of extant species within native ranges”- humans have actually increased megafauna richness to levels approaching the Pleistocene, through redistribution and rewilding.”

Wallach cites several examples of invasive species who have “benefited the world”, reminding us that there are species who have “proven resilient to control” (killing), that “now exist mostly or solely in the diaspora” (un-native environments) – proving the fact that invasive populations serve as “critical buffers against extinction”.

(A partial list of invasive species who have benefited non-native environments can be found in an article written by Merritt Clifton titled, “Aussie prof challenges ‘invasion biologists” on their own turf.”)

Fleming’s quarrel with Compassionate Conservation comes full circle with his attacking the idea that “individuals matter”. He defends his position by quoting New Zealand ecologist, biologist, and researcher Graeme Caughley, who said:

“I have no strong feeling for individual wild animals although paradoxically I cried when the family cat was run over. I get very emotional about the suggestion that a population of wild animals should be exterminated. Hence I am a conservationist but not an animal-liberationist.”

Fleming closes by identifying himself as “a lower case compassionate conservationist (i.e. a conservationist with compassion), and musing that “I am a living animal and every meal I eat compromises the life of another animal or plant. All things come with a cost, so I guess I’ll just have to get used to it: ‘Such is Life’.”

I find Compassionate Conservation not nearly so nihilistic. Even as Fleming admitted, I am encouraged by the realization that compassion may be a uniquely human characteristic and given our responsibility for and place in the environment, I can’t help but wonder if our possession of this uniquely human attribute is not an accident – and that we should use it, before we lose it…

2 Replies to “Is compassion ever misplaced? by Ed Boks”

Comments are closed.