I’ve been devoting a considerable amount of time to understanding a rapidly growing international and cross-disciplinary movement called Compassionate Conservation.

This movement promotes the protection of wild animals as individuals within conservation practice and policy – using four guiding principles: 1) First, Do No Harm; 2) Individuals Matter; 3) Value All Wildlife (which I took the liberty of expanding to Value All Life; and 4) Peaceful Coexistence.

While watching the (recommended) documentary, “Predator/Prey – The Fight for Isle Royale Wolves” it occurred to me a fifth element might help better define Compassionate Conservation as a discipline, and not just a philosophy. That element is “Stewardship”.

Merriam-Webster defines stewardship as the careful and responsible management of something entrusted to one’s care. Over the years, my understanding of “stewardship” has been influenced by the writings of Matthew Scully.

In his book, “Dominion – The Power of Man, the Suffering of Animals, and the Call to Mercy” Scully says, “Animals are more than ever a test of our character, of mankind’s capacity for empathy and for decent, honorable conduct and faithful stewardship.

“We are called to treat them with kindness, not because they have rights or power or some claim to equality, but in a sense because they don’t; because they all stand unequal and powerless before us.

“Animals are so easily overlooked, their interests so easily brushed aside. Whenever we humans enter their world, from our farms to the local animal shelter to the African savanna, we enter as lords of the earth bearing strange powers of terror and mercy.”

Terror and Mercy

The words, terror and mercy, respectively describe the two methods of conservation competing for legitimacy in the fields of science and the court of public opinion: traditional and compassionate conservation.

Traditional Conservation finds its roots in the religious belief of a once perfect Garden of Eden, from which nature has “fallen” as a result of man’s sin. Traditional conservation seeks to “restore” nature to that idyllic (and unknown) state by eradicating any species that “invades” any environment where it is not native.

The tools of Traditional Conservation are terrible indeed – requiring a tortured reasoning to justify the contra-intuitive strategies of “conservation” by eradication – methods which include, but are not limited to hunting, bounties; introduction of viruses and disease; poisoning; trapping; and ripping.

While watching the aforementioned documentary, “Predator/Prey”, the narrator attempted to explain the intention of Traditional Conservationists to “restore” the environment on Isle Royale – but the explanation begged the question, “Restore to what?”

Man’s influence on Isle Royale can be traced back 6,000 years. Who among us can determine how far are back we must to go to “restore” this island, or any environment, to a pristine condition? In a world of constant change, caused by man or by nature itself, how can we possibly define, much less achieve, a “pristine” state?

The fatal flaw in Traditional Conservation, it seems to me, is the proclivity to exclude man from the equation. A point addressed in Predator/Prey when one of the commentators agrees with the proposition that man “should just allow nature to take its course” with the proviso that “yes, and I am a part of nature.”

Man’s impact on the environment is often described as good or evil, whether that impact was deliberate or not. Compassionate Conservation, as I have come to understand it, suggests that man is capable of making compassionate choices within the parameters of the four Compassionate Conservation guiding principles. I humbly submit for consideration the addition of “Stewardship”.

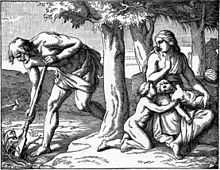

Man’s earliest understanding of his responsibility for the environment may be found in the Book of Genesis:

“And God said, ‘Let us make man in our image, after our likeness; and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.’”

“And God prepared the man in His image; in the image of God He prepared him, a male and a female He prepared them. And God blessed them, and God said to them, `Be fruitful, and multiply, and fill the earth, and subdue it, and rule (take dominion) over fish of the sea, and over fowl of the heavens, and over every living thing that is creeping upon the earth.” – Gen: 1:24-28

Unpacking “subdue” and “dominion”

In Hebrew the word “subdue” is kabash – (now you know where that word comes from). Kabash means “subdue” or “enslave”, and even “molest” or “rape.” But there’s a catch: this word is only applied to a hostile party, such as a military enemy.

To not subdue a hostile enemy could lead to death. Hence, the injunction to subdue the earth is to ensure we don’t starve. This is further explained in Gen. 3:18-19 where it says, “Thorns and thistles [the earth] will yield you… and by the sweat of your brow you will eat your food…” In this context, subduing the earth has to do with clearing the land for agriculture to ensure we have enough food to eat.

The Hebrew word for “dominion” is radah. It’s a royal word referring to the rule of a king; and is used in Psalm 72:8, referring to the coronation of King Solomon: “May he have dominion [radah] from sea to sea . . .”

However, verses 12-14 reveals what dominion [radah] is supposed to look like: “He delivers the needy when they call, the poor and those who have no helper. He has pity on the weak and the needy, and saves the lives of the needy. From oppression and violence he redeems their life; and precious is their blood in his sight.” (NRSV)

By way of contrast, an example of improper dominion [radah] is described in Ezekiel 34:4, where God rebukes a king for “not strengthening the weak, or healing the sick, or binding up the injured, or bringing back the strayed, or seeking the lost, but [instead[ with force and harshness you have ruled [radah] them.”

The word “dominion” has always meant taking responsibility to protect the defenseless and administer mercy to the oppressed.

Applying this meaning to the injunction to exercise dominion over creation, we understand that our privilege to rule over the environment is equal to our responsibility to protect it.

So my study of Compassionate Conservation has helped me to understand that effective conservation has little to do with lethal efforts to return the world to some illusionary pristine state, and more to do with taking responsibility for the world as it is – which means to take responsibility for the needy, those who have no helper, the weak, sick, injured, strayed, lost and oppressed. This is what dominion and compassion requires.

Therefore, I humbly submit an amendment to the guiding principles of Compassionate Conservation to include Stewardship:

- First, Do No Harm;

- Individuals Matter;

- Value All Life;

- Peaceful Coexistence; and

- Stewardship

One Reply to “Traditional and Compassionate Conservation: a study in terror and mercy by Ed Boks”

Comments are closed.